135 Years of Great Design

Our History

“Experience Knowledge“

On a spring morning in 1837, three brothers left their small farming village in Germany and set out for the port city of Bremen. They were on their way to cross the Atlantic and make a new home in America. The oldest, Adam, was only 20. Edward was 15, and Henry was 11. Their tenant-farming parents and their infant brother stayed behind, counting on the three sons to find them all a better life in the New World of opportunity that beckoned like the mythical Horn of Plenty.

It was a 61-mile trek from their little town of Belm to Bremen, where they purchased passage on a ship bound for Baltimore, 4,000 miles across the Atlantic. Today, such a journey by boys, young and alone, crossing an ocean to an uncertain destination with no support from home and family, would be almost inconceivable. What they experienced on their eleven-week voyage was probably unimaginable. The mass migration from Germany to America was just beginning. But already, the ships were cramped, airless “floating coffins,” reeking and infested with rats and disease.

Adam, Edward and Henry Greiwe left home on May 1, and arrived in America on July 13, 1837. They rode the first trickling stream that soon became a flood of immigration. Just a few years later, by 1850, the U.S. population had swelled by more than a third in ten years as the tide of immigrants poured in. More than 1 million were Germans, who had good reason to flee their country. They were oppressed by a cruel, decaying monarchy; their country had been ravaged by the cholera epidemic of 1832; and the Famine of 1845 sparked rebellion and bloody revolutions across Europe.

After landing at Fells Point in Baltimore, the second busiest immigration port behind Ellis Island in New York, the three brothers found their way to Cincinnati — which was even then becoming known as “Zinzinnati,” with a population that was 41 percent German by 1900. The Greiwes settled in a part of town still known as Over-the-Rhine, named by German immigrants who thought the Erie Canal that ran through the middle of the city looked like their own “little Rhine.”

Their parents, Everhard Heinrich and Anna Maria, soon followed with their youngest son, Christian. Before long the whole family was in business in the Pendleton neighborhood of Over-the-Rhine, living and working in the shadow of their solid-brick anchor of faith, St. Paul’s Church, which the Greiwe brothers helped found and build as other nearby Catholic churches overflowed with immigrants.

They also built impressive homes near their church, ran their businesses and raised their families. Their hard work and success were typical of millions who came to America, “yearning to breathe free,” as the Statue of Liberty’s poetry says. The Greiwe family story became intertwined with the history of Cincinnati like a vine growing through a wrought-iron trellis. They became expert builders, respected doctors, real estate developers, tailors, grocers, craftsmen and hardware store owners.

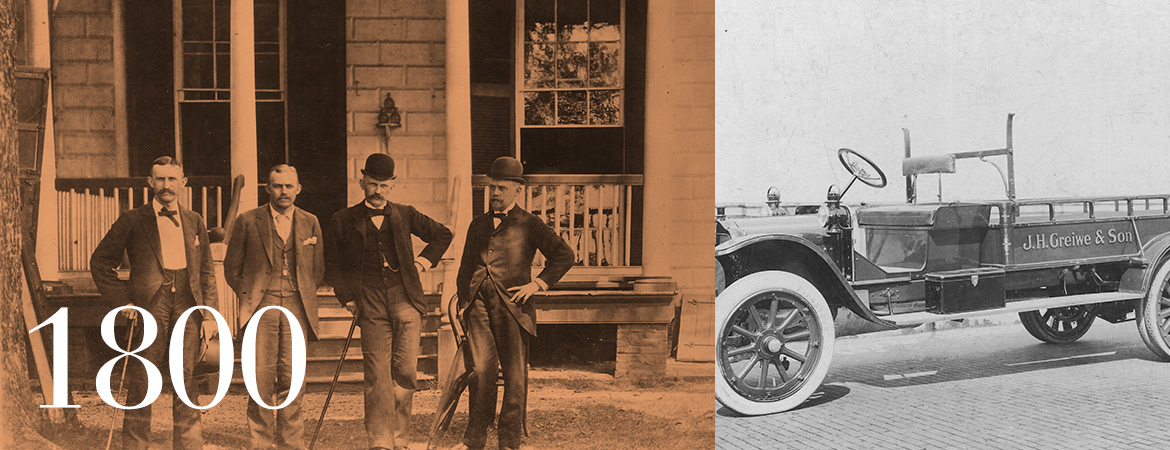

The oldest brother, Adam Greiwe, became a U.S. citizen in 1839 and married another German immigrant, Elizabeth Lietemeyer. In 1866, he went into the hardware business and sold stoves and tools from a store at the southeast corner of 12th Street and Broadway. Adam and Elizabeth raised three sons and a daughter.

Their second son, John Henry, started a painting business in 1881 with partner Henry Inderhees: Greiwe & Inderhees. They began with two painters and expanded to 14 painters by the end of their first year. They moved the business three times to keep up with growing demand, finally building their own two-story shop at 1025 Broadway. Their specialty was interior decorating – especially hand-painted murals, wall panels and effects that graced the homes of the wealthy long before wallpaper was common. Soon they added decorative plaster and other home design services.

Greiwe may very well be the longest continuous family interior design firm in the United States. The only rivals for that distinction are department store interior design firms dating back to the late 19th Century. And none of those are still in business.

When Inderhees fell ill, John Henry Greiwe took over and renamed the business Greiwe Decorative Company in 1896.

The year is important. A New York City firm, McMillan Interior Design and Decoration, has long claimed to be the “oldest full-service interior design firm in America,” founded in 1924. Greiwe Decorative Company dates back to 1881.

Prof. Patrick Snadon, who teaches the history of architecture and interior design at the University of Cincinnati school of Design, Architecture, Art and Planning (DAAP), says it’s no surprise that the Cincinnati company was among the first and is now the oldest of its kind in the U.S. “One of the things about interior design firms is that they emerge from the craft decorating profession, where they not only did design but also did installation work, such as draperies, upholstery, cabinetry, furniture and painting.”

That’s also how Greiwe Decorative Company got started.

There are several reasons why Greiwe Decorative Company led the way and remained successful. “First, in the middle of the 19th Century, Cincinnati was an extraordinary center of furniture production. From 1840 to 1850 was its high point on the national scene,” Professor Snadon says.

The local specialty was Art Carved furniture, hand-made in the style of the Arts and Crafts movement (1880-1910), which was a rebuttal to increasing industrialization and factory-made furniture. As Cincinnati furnishings made a national reputation, Greiwe led the way for interior design. Their hand-painted decorative murals remained popular in Cincinnati long after other cities were using manufactured wallpaper.

Murals and decorative works painted by Greiwe craftsmen are still being discovered in historic homes in Cincinnati. A good example of those murals surfaced during preservation of the Hauck House, a historic landmark built in 1870 by one of Cincinnati’s most successful brewers.

“It does seem that Cincinnati patronized those decorative hand-painted murals to a much larger extent than other regions of the U.S.,” Snadon says. “There was a big artist community supported in Cincinnati. Cincinnati was very important but unrecognized for interior design in America.”

The famous Taft House, built in 1820 and considered to be one of the finest examples of Federal architecture in the Palladian style, was one of J.H. Greiwe’s earliest jobs. In 1898, Greiwe Decorative Company painted the 32-room mansion for $230.

Even earlier, before the Civil War, the stately home was the residence of Nicholas Longworth, the city’s leading banker and internationally famous winemaker. He hired local African-American artist Robert Duncanson to decorate the entryway with spectacular hand-painted landscapes. That probably sparked imitation by other wealthy homeowners, who hired Greiwe Decorative Company. Longworth was an influential patron of arts, and his trend-setting style created demand for decorative mural painting. Fittingly, the Taft House is now one of Cincinnati’s finest art museums.

Interior design was well established in London as early as the 1850s, but did not really catch on in America until after the Civil War. America’s first influential book on the topic, Decoration of Houses by Edith Wharton and Ogden Codman, was published in 1897. It introduced a more American style that rejected the heavy draperies, gloomy dark wood, decorative clutter and overstuffed furniture of the Victorian era, and introduced a more practical, informal, personalized design.

That new American style was later advanced by one of the first popular American interior designers, Elsie de Wolfe, in her 1913 book, The House in Good Taste.

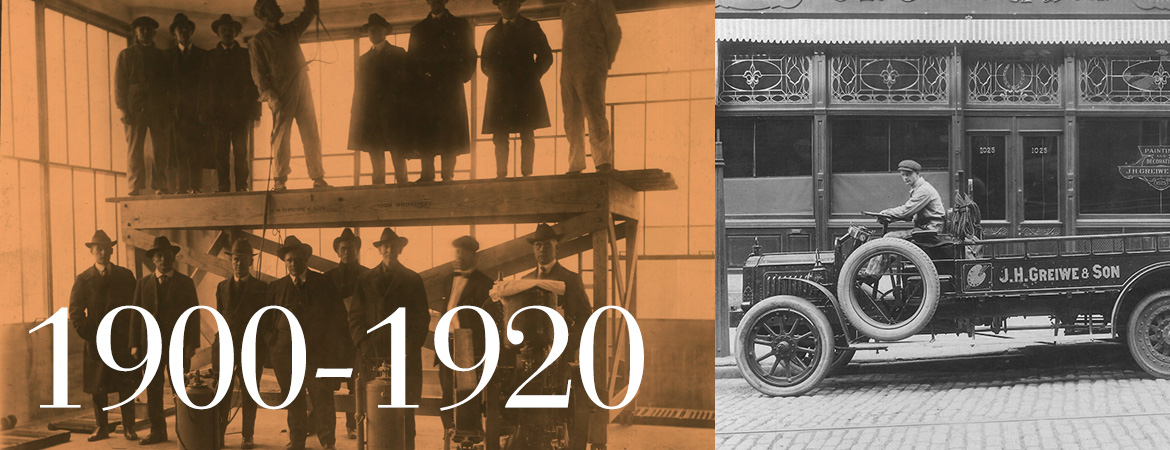

In the late 1800s, Greiwe Decorative Company was “a turnkey operation,” with a full menu of home-design services from more than 200 employees: cabinet makers, drapery designers, fabric specialists, fine refinishing, upholstery, carpeting consultants and more than 100 painters, including highly skilled artists who created beautiful murals and still-life scenes for homes and churches.

John Henry Greiwe, known as “J.H.,” was a tough taskmaster who started his workday at 5:30 a.m. and left his office more than fourteen hours later at 8 p.m. According to family legend, he would dismiss a painter who showed up for work – at 40 cents an hour – in a soiled uniform. J.H. mixed his own paint to his own exacting standards.

Another example of J.H. Greiwe’s “economy” were his Sunday visits to the company office, where he would collect discarded paper from wastebaskets and cut it into notepads for company secretaries and clerical staff.

Among his early contracts was the rescue of the family church that his father and uncles had helped found and build, St. Paul’s. In 1895, J.H. launched a redecorating project that included decorative painting and 24-karat gold leaf. As the project was being finished in 1899, a fire swept through the church, almost destroying it. All of the valuable gold leaf was lost. But J.H. repainted and repaired the scorched church interior for $861, according to company ledgers. A year later, the widow of Adam Greiwe donated $1,000 to the church’s Golden Jubilee.

“Experience Knowledge“

J.H. Greiwe wanted to expand to the fast-growing wealthy suburbs beyond the downtown area, but he had to decline those jobs because it took three hours or more for his horse-drawn wagons to get to the homes of potential clients in Indian Hill and Glendale. Just delivering supplies and workers consumed most of a day, and the horses were worn out by the round trip.

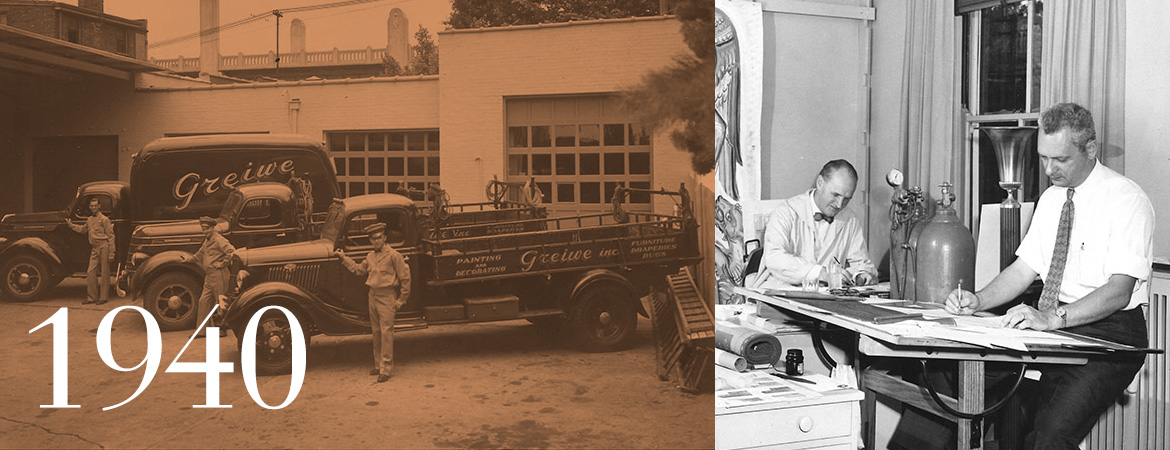

So the company bought its first truck, a Packard, with a long flatbed that stayed in service on various truck frames for 45 years. Hand-painted gold lettering along the side read: “J.H. Greiwe & Son – Painters & Decorators.”

The family’s longtime delivery driver, Eddie Bescher, hired after he quit school, had a reputation for racing his teams of horses against other horse-drawn wagons. But with the purchase of the first Packard truck, he was soon wearing polished tall leather boots and chauffer livery. A new Pierce Arrow truck was added as the business grew. Both trucks had custom chromed grilles and bumpers, and prestigious gold-leaf lettering.

With the new fleet of trucks, the company was able to reach clients beyond the Southwest Ohio market. J.H. Greiwe & Son proudly advertised that they had a hand in painting and decorating almost every important private and public building in Cincinnati. Among the local landmarks that were given the Greiwe treatment: Isaac Wise Temple, Music Hall, the Alms Hotel and the home of legendary politician George “Boss” Cox, whose political machine ran Cincinnati from 1885 to 1905.

In those days, painting was not the simple roller and brush coat of latex we think of today. Customers wanted color and beauty far beyond a few limited patterns of wallpaper. Painters would start by stippling and mottling walls to add texture before they were tinted. After a Greiwe artist painted a fruit basket, flowers or garden scene, the walls had to be starched so they could be washed later without damaging the paint.

A few historic Cincinnati homes from that era still are adorned with the colorful, intricate floral designs, geometric patterns and morning-glory vines that were hand-painted on cornices, ceilings and walls, the signature designs of J.H. Greiwe & Son. One of the artists who painted those designs, German-born Dyonis Prechtl, once said, “I planted a million flowers in bedrooms.”

“Experience Knowledge“

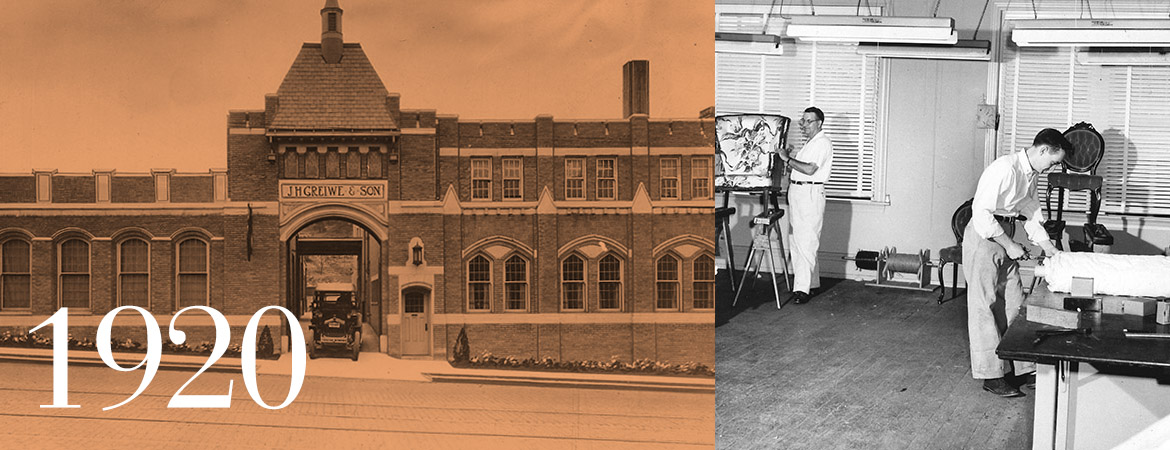

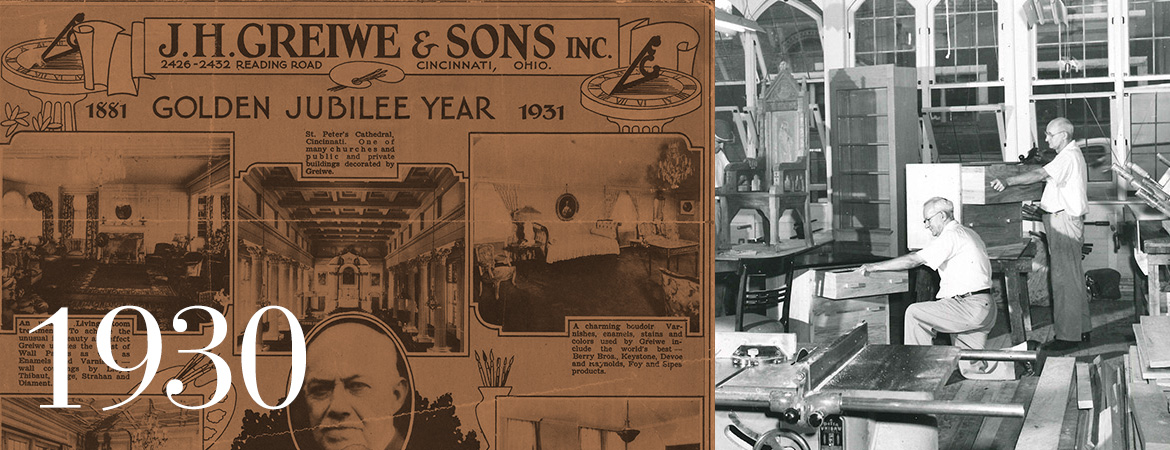

The business prospered along with Cincinnati’s population and economy. Eugene “Gene” Greiwe, the youngest son of J.H., went to work in the family business in 1920 for $3 a week. He was 21, a new graduate of the University of Dayton. The next year, in 1921, the company relocated to an old pottery factory at 2426-36 Reading Road, where it remained for fifty years.

The new offices had room for a paint shop, upholstery, cabinet shop, furniture refinishing and showrooms to display samples of carpets, rugs and fabric for potential clients. The well-known craftsman Enrico Galastri supervised the large crew of a hundred artists and painters.

As wallpapers became more popular, Gene led an expansion into more interior decorating, with J.H.’s reluctant approval. It was a big success. Painting gave him a natural opening to suggest fabrics, carpets and furnishings. Soon ceiling ornaments and decorative plaster were added as options for home designs.

But later that year came economic catastrophe with the stock market crash of 1929. The world changed dramatically overnight. J.H. Greiwe & Son had its own grim chapter in the tragic story of financial collapse written across America. The decorative plaster business failed. With few new homes being built and families struggling to keep up with their mortgages, remodeling and decorating jobs dried up like crops in the parched Dust Bowl. J.H. Greiwe & Son sold half of its business and changed its name to Greiwe Inc.

“Experience Knowledge“

Gene Greiwe became general manager of the company in 1930 at a salary of $50 a week. In 1935, the Greiwe interior decorating shop was cut in half and the decorating staff was reduced. Then Cincinnati was hit by the Flood of 1937. As Cincinnati dug its way out, so did Greiwe Inc. During the hard times, deposits were mandatory before starting work – and delinquencies in payment were not uncommon.

When Gene was hired to redecorate a home that had been damaged by fire, he met his future wife: Elizabeth Van Lahr, daughter of Provident Bank President Leo J. Van Lahr.

Gene’s sense of humor, outgoing personality and ability to make friends wherever he went soon added to the company’s clientele. He was a familiar, well-loved and impeccably dressed regular at Cincinnati social events.

“Experience Knowledge“

Innovator, founder and patriarch J.H. Greiwe passed away in 1941, leaving the business to his son Gene.

“He was very, very tough businessman,” grandson Bob Greiwe recalled of J.H. “Tighter than a drum. He supplied all the paintbrushes. If you asked him for a paintbrush at 6 a.m. when you got to work, he would say, ‘Here’s a good brush. Now give me your watch. You will get your watch back when I get the brush.’ He was not what you’d call an amiable kind of person. But J.H. was smart enough.”

As the new CEO, Gene had to struggle along with all business owners during World War II, to cope with rationing and constant shortages. As the nation went to war in 1941, Greiwe Inc. painted camouflage schemes on tanks. After the war, the company made an effort to hire war veterans.

His sons, Dick and Bob, remembered Gene playing ball with them in the evenings in the side-yard of their Indian Hill home on Blome Road. “He would hit baseballs to Bob and me,” said Dick. On summer Sundays, Gene occasionally organized baseball games on the Blome Road farm with his friends. “There was never a game without a cold keg of beer at second base,” Dick recalled.

As boys, Dick and Bob stayed busy exploring a creek, racing sleds, playing games with the Castellini kids who lived nearby, playing football, reading comic books, listening to the radio and pounding a punching bag in the basement with a constant thumping until their mother had had enough and made them stop.

They also worked hard shoveling snow, raking leaves and working in the huge family garden. “We raised everything that would grow,” said Dick. “One year we raised a hundred quarts of raspberries that were sold to a local grocery for 15 cents a quart.” One of his least favorite chores was to mow five acres with a power push mower – an all-day job.

One year Gene gave the boys each a sack of potatoes to plant. Dick manicured his patch every day while Bob let his grow wild with weeds. “Wouldn’t you know it, when it was time to harvest, Bob had nice full-grown potatoes ready for the market and my patch produced tiny little marble potatoes,” Dick said.

He remembers his father fondly in those years. “He’d come home, have a drink in the living room with his wife, fall asleep in his chair for a while then go to dinner. He worked hard. Just a great guy, a great mixer, a great person and a funny guy.”

“Experience Knowledge“

The post-war years brought a new generation to the family business. Dick graduated from high school in 1948 and was awarded a football scholarship to the University of Cincinnati. He studied design in UC’s Applied Arts Program (which became Design, Architecture, Art and Planning, or DAAP, in the 1970s). Dick left UC after a year and a half to enroll in Parsons School of Design in New York, where he graduated in 1952. He was greatly influenced by the guidance and mentoring of Parsons legends such as Van Day Truex and Albert Hadley. During his years in New York, Dick worked trade shows without pay just to learn the business, and visited many homes of well-known designers such as Billy Baldwin and William Pahlman.

“I used to go to antique shows and work. They didn’t pay me, but I was learning, and I had the opportunity to go to art shows and museums on my own,” he remembered. “But there were times when I wondered ‘What the heck am I doing here?’ I had left a nice home in Cincinnati, a football scholarship and the woman I was going with who became my wife. It was very hard because I missed Missie so much. I would call her every Sunday night from the Howard Johnson, and I would cry every Sunday night because I wanted to get home.”

He stuck it out and graduated from Parsons in 1951. Offered a scholarship for further study in Paris, he declined and went home to join the family business and marry his high school sweetheart and “Irish cutie” Missie McCarty.

His younger brother Bob followed right behind Dick. He graduated from high school in 1950 and spent one year at Parsons School of Design, then returned to Cincinnati to finish his degree at UC’s Applied Arts Program, graduating in 1953. He was active in Sigma Chi Fraternity as president. He also joined the family business almost immediately after graduation.

Their father never pressured his sons to join the family decorating business. But growing up over the years, they had heard his stories and tales around the dining room table. They were excited by the challenge and the opportunity to continue the Greiwe & Sons tradition.

During the next ten years, Greiwe Inc. began to find work doing interior decorating of churches. Stained-glass craftsman Glen Willis and Professor Karl Reischel, who was formerly head of the architectural department for the historic city of Budapest, Hungary, became part of the Greiwe team. They brought expertise in ecclesiastical symbolism and stenciling, created prospective drawings and helped with research. Later, architect Edward Schulte was added to the team, along with Earhard Stoetner of Milwaukee, who was a skilled craftsman with stained glass and mosaics.

In the mid-1950s, Gene Greiwe was hired for the restoration of Cincinnati’s historic St. Peter in Chains Cathedral in downtown Cincinnati, originally built in 1841. During that project, Gene became good friends with Archbishop Karl Joseph Alter, who led the Cincinnati Archdiocese from 1950 to 1969.

Archbishop Alter established ninety-eight churches in the Cincinnati Archdiocese, and recommended his friend Gene Greiwe for church remodeling to all of the priests under his authority. He would occasionally stop by the Greiwe home unannounced on a Sunday afternoon. “He would pull up in his chauffeur-driven car,” Dick Greiwe recalled. “He and my dad were good friends, but those visits didn’t go well with my mother because she would be in her shorts or something, not expecting the archbishop.

“We did a lot of work on Archbishop Alter’s house, too. I remember lots of red-flocked wallpaper and red carpet.”

“Experience Knowledge“

As the church business spread nationally, Greiwe decorators worked on more than a hundred churches, including jobs in Montana, Pennsylvania, Michigan, South Dakota, Florida and Texas. Church decorating became a staple of the business and led to contracts in the commercial painting industry. Greiwe Vice President Joe Ulmer joined the firm in 1969 to handle commercial painting contracts, including high-rise office buildings, power plants and the George Wiedemann Brewing Company, which kept a four-man crew of painters busy full-time, all year. “It was a huge place, just impeccably clean, both the warehouse and brewery,” said Dick. “When the crew finished at one end, they went right to work and started again at the other end. We billed them every week for it.” Dick and Bob enjoyed making deliveries because they got free samples of Wiedemann beer, even before they turned 21.

Other projects included the Cincinnati Enquirer Building, the Sinton Hotel, Provident Bank, Carew Tower, the Gibson Hotel, Hudepohl Brewing Company and the enormous W.C. Beckjord Power Station southeast of Cincinnati.

Greiwe clients in those years were Cincinnati’s leading businesses: Cintas, LeBlond, Cincinnati Milling Machine, Procter & Gamble, the Cincinnati Reds and Cincinnati Bengals, Herschede, Towne Properties, Provident Bank, Fifth Third Bank, Western Southern Life, the University of Cincinnati, Xavier University, the Cincinnati Chamber of Commerce and many more.

Most of the best restaurants also turned to Greiwe for tasteful interior design: Maisonette, LaNormandie, Chester’s Road House, the Golden Lamb, King Cole and Frisch’s Big Boy among others.

Private clubs were also frequent customers, including the Queen City Club, Cincinnati Country Club, Hyde Park County Club, Kenwood Country Club, Maketewah, Western Hills, Cold Stream, the University Club, Terrace Park Country Club and more.

They worked on the Delta Queen and the Mississippi Queen Riverboats, and private yachts owned by prominent families.

They painted “The Little Mermaid” at the bottom of a client’s swimming pool, and installed a whirlpool bath in the middle of a master bedroom for a woman who was confined to a wheelchair.

When St. Francis de Sales Church in Cincinnati hired Greiwe to hang twelve murals of the Apostles from the cavernous ceiling, ninety feet above the pews, Gene dropped by the jobsite one day and was alarmed to find Dick and Bob up in the dim rafters, climbing the scaffolding with the work crew.

“He walked into the church and said, ‘Where’s Dick?’ When he found out where I was he yelled, ‘You get down right away!’ I guess when you’re 19 years old, nothing scares you, that’s just your job,” said Dick. “Those guys I worked with, at noontime they would have races down the scaffolding to see who could get down faster.”

Dick and Bob were busy in those years establishing their own clientele, as Gene slowly introduced them to the intricacies of the decorating business and gave them increasing job challenges. As Dick and Bob took on bigger roles, the 1950s were an exciting time of fresh new design and innovation. The interior design part of the business grew rapidly. Greiwe Inc. became a training ground for young designers, and earned a national reputation. George Hofmann was instrumental in growing the Greiwe interior design department with a staff of highly qualified designers.

In 1962, Gene appointed Dick as president and CEO, and Bob became vice president.

“Dad was not a designer, but he sent both of us to design school,” said Dick. “He didn’t really get into the design part of it. He never went on my jobs. In the beginning when we first started we had a lot of people who asked me to come to Avondale or Clifton, because they wanted a designer to come to their home and give them advice. It took up a lot of time, so finally I said, ‘I’m going charge a consultation fee.’ Dad said, ‘You can’t do that, you’re only 22. They won’t pay you.’ But I said I was going to charge $5 an hour. I did and they paid me. Dad couldn’t believe it.”

Among the biggest projects in those years was a new Cincinnati restaurant that opened in 1966: The Maisonette. Dick Greiwe did the interior design and traveled to Paris with the owners, Lee and Joan Comisar, to find the ideal furnishings, including an antique bar that became the setting for countless business deals, friendships and love affairs in Cincinnati. The Maisonette soon became a national landmark, the must-see jewel in the crown of the Queen City. By the time it closed in 2005, it held the world record for the longest streak of five-star ratings in the Mobil Travel Guide: Forty-one years of excellence as one of the world’s greatest restaurants.

While Bob Greiwe built a successful specialty business designing interiors of banks and offices, Dick went after and landed a dream job: Interior design of a spectacular mansion named La Lanterne.

A book owned by the Indian Hill Historical Society, From Camargo to Indian Hill by Virginia White, describes famous and historic homes in Cincinnati’s most exclusive neighborhood. It says:

“La Lanterne, an exquisite two-story 17th Century reproduction French manor, was patterned after the original La Lanterne near Versailles, France. This prototype was the residence of the Count of Poiz, military governor of Versailles during the reign of Louis XVI. This graceful American adaptation was designed by Mathew H. Burton and built in 1929 for Mrs. Norma Wendisch Sullivan.”

The home, still standing, is symmetrically balanced, with a cobblestoned circular drive that surrounds a landscaped island with a fountain in the center. Black wrought-iron gates and fencing surround the property, which stretched over 38 acres of formal gardens that echo the palace gardens of Versailles.

When Dick heard that La Lanterne had been sold and was being remodeled, he contacted the owner, corporate executive Mike Schieble. “He didn’t want to hire me. He already had two designers. I called him and said, ‘Mr. Schieble, I can get your job done better than anyone else in town. I know all the elements, I’ve been studying the period.’ He said no. So I asked, ‘Can I just get an interview?’ Finally, he said OK, and after the interview I got the job. I was so happy because I knew I could do it right.”

That led to a friendship and unexpected adventures, Dick recalled. “Mike Schieble was brought here as president to run American Standard. He looked like Clark Gable and had a beautiful wife, but he wouldn’t let her participate in any decisions. ‘You and I are calling the shots and we’re going to get this done,’ he told me.”

Dick was soon traveling to New York to find artwork and furnishings for the design. “I was so impressed that he trusted me to go on my own.”

The remodeling spared no expense: marble floors, exotic hardwood parquets, breathtaking draperies, stained glass windows and a wrought-iron fence topped with hundreds of gold-leafed arrow points.

“It had parquet floors just like Versailles, and curved railings for the staircases made of custom bronze, which was hard to do. When we worked there we wore ‘scuffies,’ cloth shoe covers we put on our feet so we would polish his marble floors.”

When Schieble decided to decorate the walls with French boiseries—hand-made, carved paneling—Dick was sent to track them down. “We found them but they were thousands and hundreds of thousands of dollars. So we made them in our shop.” He consulted with renowned designer Mildred Irby in New York to make sure their design was correct. “They were built and finished and gold-leafed in our shop, and when we put them in they fit. Because they had to.”

One day Schieble called Dick and asked, “I’m going to New York to buy a Monet. Want to come along with me?” Dick didn’t hesitate. “We got there and they brought this Monet out. It was lily pads, one of the famous ones, and he bought it and took it home. He told me, ‘I just wanted you to be here because you will never see someone buy something like this again.’ And he was right about that.”

Dick designed homes for wealthy clients in Cincinnati and Florida, but he never had a project again quite like La Lanterne. “They all had their own look. It was great doing them. When they were done I moved on. But oh, to see them again in their glory.”

Among his favorite stories from those years: When a Greiwe Interiors crew was sent to do some touch-up work at the Hopewell Road home of DeWitt Balch, the elderly widowed owner, Elizabeth Balch, asked one of the painters to help her get some groceries. “She liked him so much she kept him on for two years as chauffer, chief cook and bottle washer and whatever else needed to be done,” Dick recalled. “And he stayed on our payroll. We billed her every month.”

And Dick still laughs about the time a trucker refused to carry a large sofa into the showroom and insisted he would leave it on the curb. A resourceful Greiwe secretary was the only one in there at the time and needed that sofa brought inside. The driver refused until she offered to flash her breasts. The sofa was delivered – inside the studio.

In 1966, Bob was commissioned to restore and paint the interior of the Ohio State Capitol Rotunda in Columbus. As part of the job, they were asked to hand paint the thirteen-foot diameter State Seal that adorned the ceiling. The only model was a matchbook with a one-inch seal on the cover.

“We made up our own design and rendering, which was used by the state, and the large canvas was painted in our warehouse on Reading Road by Nelson Slater and Italian artist Dyonis Prechtl,” Bob said.

As he researched the project, Bob found several different designs of the “official” state seal that were being used throughout the state. The version he finished, incorporating the best elements of the various designs, was approved by the Legislature and became the true official seal of the State of Ohio, enshrined in a law passed by the Ohio General Assembly in 1967 and signed by Ohio Gov. James A. Rhodes.

“Experience Knowledge“

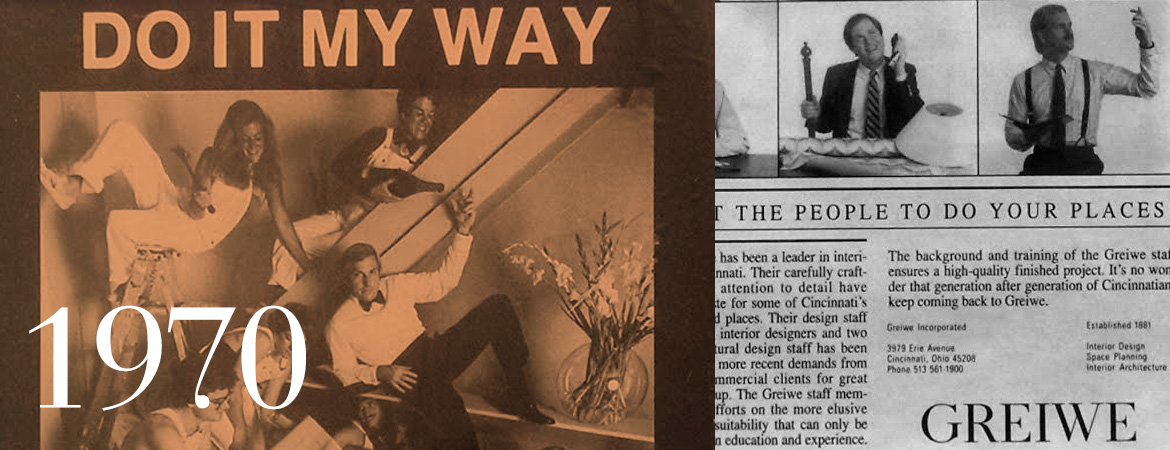

As the decade dawned, the U.S. economy entered a recession that spilled over into the 1980s. Inflation that had averaged 2.5 percent for seventy years soared to more than 7 percent, while interest rates climbed to 12 percent. Home mortgages at 14 percent and higher soured the housing market.

Greiwe Interiors Inc. hit rough times. Gene had a heart attack in 1970 and retired. A poorly estimated bid to paint DuBois Tower in Cincinnati stressed the company finances and raised genuine worries about the future.

Bob recalls the tough decision to close down the painting business on which the company was founded. “I brought an auctioneer in and said, ‘Sell the whole thing.’ We were out of the painting business in one day. We were losing money and that stopped it.”

Elmer Schmidt took over the painting business, including the contract to paint DuBois Tower. “Elmer said he would take care of them even though he couldn’t make any money. He was a great guy,” Bob said.

Next came the decision to close down the long established upholstery, drapery and cabinet departments. Stan Riley, who had run the Greiwe drapery department for decades, took that over, along with his son, Stan Riley II. The company was whittled back to fifteen employees.

On February 1, 1971, Dick branched out with his own company, Greiwe Group III. It was tough going at first. “I was 40 when I started my business. I said life begins at 40, and sent letters to all my clients. My grandfather, Leo VanLahr, had been president of Provident Bank, so I went down to the bank and told them I needed $5,000 to start my company. They said, ‘Nope. You’re not going to make it.’ They told me I should have stayed with the company.

“I went home and told Missie, ‘I can’t believe it. My grandfather was president of Provident Bank. My Uncle Frank was president. But they won’t lend me any money. What will I do? So I called (local business leader) Joe Rippe and told him I was in trouble, and I needed $5,000. He said he would give me $25,000 if I needed it. I went in on Monday and got a check for $5,000. And I paid it back in three months.”

The new offices for Greiwe Group III were nothing like the ones he left at Greiwe Interiors. “I was working out of the backroom of my house. Missie would be getting the kids off to school and I would be meeting with clients. It was pretty embarrassing. But in six months I moved to the office on Delta.”

The Delta office was a small former dress shop. “It was tiny. Bob’s place on Erie was a Taj Mahal compared to our little shop.”

Dick’s six children remember it well. They all worked there as they were growing up, first cleaning the office, then, when they were old enough, delivering furniture and design materials on the company truck.

“They all worked. Every one of them. They would come in on Sundays. They’d say, ‘We don’t want to go down there.’ I’d say, ‘Get dressed. We’re going.’”

Meanwhile, Dick was working long, wearying hours to make his new business succeed. “We were turning stuff out like crazy. We made it, but there were a lot of tears and anguish over it. I used to say, ‘We’re making a living on it, aren’t we?’ My clients were unbelievable. They believed in what I was doing.”

As his hard work paid off and led to more jobs, he designed the interiors of spectacular mansions and Florida winter homes. His clients read like a Who’s Who of Cincinnati: Albers, Emery, Williams, Pogue, Shillito, Lazarus, Longworth, Scripps, Farmer, Gamble, Herschede, LaBlond, Lindner. His restaurant clients included Palm Court at the Netherland Plaza, LaNormandie below The Maisonette, and Chester’s Roadhouse.

A confessed “workaholic,” Dick also found time to design 22 country clubs, including Hyde Park Country Club, Camargo, Kenwood, Maketewah and Western Hills. “We had a golf group that played on Mondays with the club pros, and we circulated from club to club. That’s where I would meet the people who ran the clubs. I got a lot of jobs that way.”

Meanwhile, Bob’s business, Greiwe Interiors Inc., worked on commercial and residential design. By 1975, his Hyde Park shop on Erie Ave. offered customers 30,000 samples of fabric, 5,000 samples of carpet, 12,000 wallpaper samples and 80,000 choices in furnishings. Bob took jobs in Virginia, Indiana, Illinois, Kentucky and Florida, as well as Ohio. His clients included fraternities and sororities, banks, Riverfront Stadium boxes and Taft Broadcasting headquarters.

Gene died in 1972, leaving an empty space in the family that had been filled by his outsized personality, good humor and loving leadership.

Both brothers emerged at the end of the decade with successful design businesses. In 1974, the family business drew national attention, when Interior Design Magazine published a feature story about their history in Cincinnati.

Dick’s son Doug, the youngest of six children, was watching his father and liked the career he saw. “I think my father did his best work in those years,” he recalled. “We were on a delivery together to Sherlock’s Restaurant in Indianapolis when the client pulled me aside to tell me what a great job my father did.”

The design included ceilings hung with fabric. “The ceiling was tented, the whole big room. I looked at that and said ‘Holy cow, how did he do it?’ And then the client spent half an hour telling me how great my father is, and I thought, ‘Hey, this is pretty neat.’”

The joy and excitement of that customer made a big impression – along with the dramatic ceiling and glitzy disco dance-floor surrounded by strobe lights and more than a hundred yards of draperies. He saw his father’s work in a new light.

“The owner of the restaurant told me my father was one of the most creative men he had ever met in his life,” Doug recalled. “His excitement struck me to my core. It was at that moment that I found my passion and my future.”

Dick was surprised. “He liked to watch television all the time. I’d come home and he would be watching TV. One day he said, ‘I want to do what you do.’ I said, ‘You’re crazy.’ He was a sophomore in high school.”

Doug told his father, “If you get that much pleasure out of the work you do, I want to do that too.”

“All of our kids could draw and paint,” Dick said with pride. “Doug went to New York and picked up design right away. He does a great job. He has a lot of great clients.”

“Experience Knowledge“

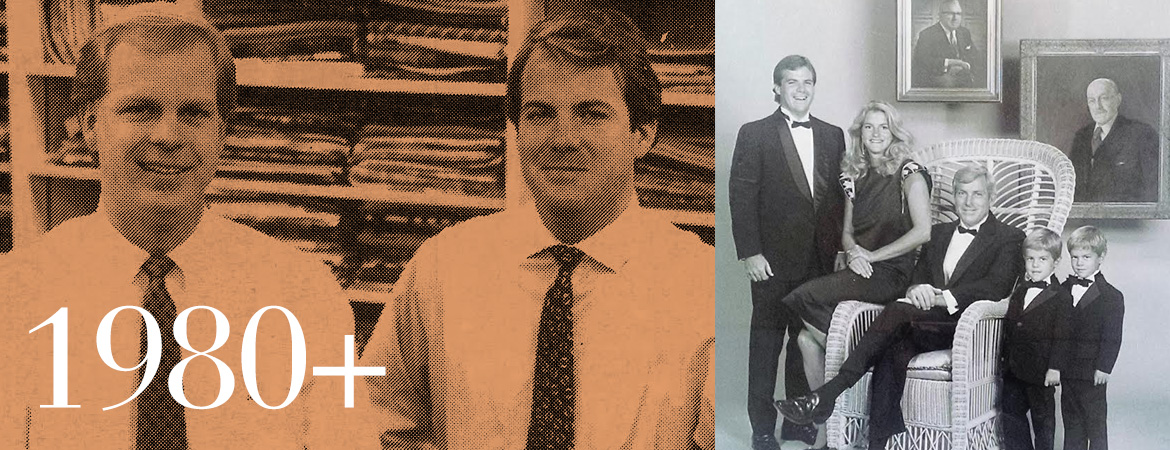

In 1984, Dick was honored by the International Design Market in Chicago and received an award for Excellence in Residential Design along with Mario Buotta.

Bob became the only interior designer who was awarded first place in all four categories of interior design. In 1996, he established the ASID Foundation for needy students and got involved in numerous philanthropic ventures for his high school and fraternity.

Bob became president and CEO in 1991 and changed the name of Greiwe Inc. to Greiwe Interiors, emphasizing an identity as designers, not decorators.

A new studio emerged in 1988, as Dick and Bob teamed up again, adding new talent to the excellent staff of designers. Greiwe Interiors remained popular and was recognized as a premier design studio in Cincinnati.

Meanwhile, Doug enrolled in the prestigious Fashion Institute of Technology in New York and completed his studies in interior design in 1984. He had career opportunities with famed interior design firms Parish Hadley and McMillen & Co., but decided to come home to Cincinnati to work in the family business and help his father, who seemed to be working himself to death.

Throughout his college years, Doug worked for his father—but only on delivery trucks. As he watched his classmates take lucrative jobs with big New York firms, he was hired as an apprentice designer at Greiwe Group III, with a starting salary of $12,000 a year.

“When I came out of college I had to live at home. My dad bought me a car to get around. Then he said it’s time to move out. I asked, ‘How can I move out on $12,000?’ He said, ‘Then go on commission.’ I did, and within a year I was making more than our top salesman.”

Doug’s brother Rick and sister Jennifer joined him at the firm.

Bob’s third child, John, had enrolled in the University of Cincinnati DAAP Architectural Department and graduated in 1985. Along with Doug, Rick and Jennifer, he joined Greiwe Interiors in 1986 – making the fourth generation of Greiwes. “Jennifer was probably the most talented of us all,” said Doug. “But after a few years she left to raise her family.”

In 1989, Doug and John persuaded their fathers to team up again.

Doug’s personality, charm and professionalism quickly became evident, while John’s abilities attracted new opportunities in the architectural field. Doug and John worked as a team for seven years until John left to pursue a new career in real estate development.

Greiwe Interiors relocated to their new studio on Grandin Road, as Doug became CEO. An unfortunate fire caused a setback for a few months, but the passion and mission quickly resumed.

Dick retired in 1995 at age 65, with a Friday afternoon party. After spending one weekend at home, he returned to his desk the following Monday and is still working at age 85, still active for twenty-five years in the Senior Olympics.

Bob retired in 1999 to pursue his hobbies, including restoration of old cars, watercolors and writing.

Since the first sons came to America in 1837, the Greiwe family has been a part of Cincinnati the same way their murals, hand-painted cornices, fabrics and home designs have been an elegant compliment to so many beautiful homes.

Today, Greiwe Interiors is a diversified family venture.

“Every generation has its own evolution of the firm,” said Doug. “I don’t like just putting wrapping paper on a square box. I like to design the box. I like to think in three dimensions.”

One of his recent jobs included a search for an iron worker with the right skill-set to make iron hardware that looks like an aspen leaf, part of a project that had a budget of $450,000 just for the kitchen cabinetry.

“I never wake up and think of reasons to stay home. I wake up and want to go to work and be creative. I love what I do.”

While Dick splits his time between the Cincinnati office and Naples, Florida, Doug is constantly on the move, traveling to client homes, shopping and collecting, flying to Europe to find the right antiques.

His motto: “You have to have a vision and see it through or it will fail.”

In 1931, the family business celebrated its first 50 years of progress by thanking the “faith and confidence of thousands of Greiwe patrons.”

Looking back on more than 135 years in business, Dick Greiwe says, “Four generations later we will continue to put the ‘WE’ in Greiwe Interiors.